On a tranquil summer morning in 1899, two men climbed into a boat by the side of Loch Lubnaig near Callander and began to row it away from the shore. They were relaxed and unhurried, although they were strangers here, and their presence could easily arouse suspicion. As the mist rose, a few snatches of conversation drifted back over the water; a heron flapped lazily away, and corncrakes continued their noisy percussion from the reeds.

On a tranquil summer morning in 1899, two men climbed into a boat by the side of Loch Lubnaig near Callander and began to row it away from the shore. They were relaxed and unhurried, although they were strangers here, and their presence could easily arouse suspicion. As the mist rose, a few snatches of conversation drifted back over the water; a heron flapped lazily away, and corncrakes continued their noisy percussion from the reeds.

When the boat reached the centre of the loch, the rhythmic dipping of oars slowed and stopped; one of the men began carefully to lay out the equipment he’d stowed in his knapsack while the other set about winding a long line over the side.

A fishing trip, you might think, and nowhere better to enjoy it than the glorious landscape of the Trossachs. But the truth is far more surprising.

The men were Sir John Murray, a renowned and well-travelled oceanographer; and Fred Pullar, 22-year-old son of Murray’s good friend Laurence Pullar of Perth. And, far from idling their time away in pursuit of brown trout, they were following a strict scientific routine. With persistent dedication and the kind of hardiness that laughs in the face of wind, rain, sunburn and voracious midges, they were undertaking the Bathymetrical Survey of Scottish Freshwater Lochs.

The men were Sir John Murray, a renowned and well-travelled oceanographer; and Fred Pullar, 22-year-old son of Murray’s good friend Laurence Pullar of Perth. And, far from idling their time away in pursuit of brown trout, they were following a strict scientific routine. With persistent dedication and the kind of hardiness that laughs in the face of wind, rain, sunburn and voracious midges, they were undertaking the Bathymetrical Survey of Scottish Freshwater Lochs.

“In all of the lochs serial temperatures are taken, collections of the plankton are made by means of silk tow-nets dragged through the water at various depths, deposits from different depths are obtained and preserved; observations on the colour and transparency of the water are made by means of submerged discs, the physical features of the land surrounding the lochs noted and photographs taken.”

Making thousands of scientific recordings repetitively and consistently was a task that required skill and patience, and luckily John Murray was the perfect man for the job. A naturalist on the Challenger voyage of 1872-76, he had sailed through the Strait of Magellan, explored the turquoise lagoons of Fiji, and had brought back the first ever photographs of Antarctic icebergs. But he also believed that an undiscovered world of science lay closer to home, in the depths of Scotland’s lochs, and between 1897 and 1907 he and his small band of assistants surveyed an incredible 562 of them, from Orkney right down to Dumfriesshire.

For the depth soundings, they used an ingenious device that was designed and built by Fred Pullar whose father, Laurence, was director and principal funder of the survey. Fred’s invention was a pulley system by which up to 1,500 feet of galvanised steel wire, weighted at the end, could be wound down into the water; a clamp secured the device to the side of the boat. Measurements were taken at regular intervals, and by this means a profile of the loch could be built up, enabling its contours to be illustrated on a map.

“The Pullar sounding-machine was used in all the larger lochs, but for small hill-lochs, difficult of access, it was found advisable to construct several small machines… which could be carried in the hand or on a bicycle, and be easily attached to a rowing-boat.”

As they travelled the length and breadth of Scotland, Murray and his companions were largely welcomed by the people they encountered, many of whom were understandably curious about what these newcomers were about. In a few places, however, folklore had preceded them by at least a thousand years, meaning that generations of families had grown up in the absolute belief that their local loch was bottomless. On these occasions, Murray found himself with the rather awkward task of having to explain that it was not, and his verdict was often received in offended silence.

Sitting in a boat all day long on a Highland loch at the height of summer doesn’t sound like too much of a hardship, but there was work to be done and Murray’s team were certainly kept busy. They even witnessed a seiche (pronounced ‘saysh’), the first to be recorded in Great Britain: sounding more like a beast of Celtic myth, this is in fact a standing wave which occurs naturally in all bodies of water, in response to changes in wind speed and atmospheric pressure. It is described in the entry for Loch Treig in Inverness-shire:

“I noticed that certain stones on the shore were covered and uncovered by the water with great regularity… Mr Parsons and I found that the amplitude of the seiche was nine-sixteenths of an inch and that the period was nine minutes.”

By the time Murray had finished, he had taken over 60,000 depth soundings and described more than 700 species of fauna and flora, including 450 invertebrates and nearly 200 algae. At least 29 of these were new to science, and a further 50 were not previously known to exist in the British Isles. The deepest loch was confirmed to be Loch Morar, at 1,017 feet, which is so deep that the Eiffel Tower could fit in it with 33 feet to spare. Loch Lomond was shown to have the greatest surface area, while Loch Ness had the greatest volume of water (263,162 million cubic feet). If a monster had been lurking in the watery gloom, Murray and his friend would no doubt have been poised to measure it, but sadly Nessie declined to make their acquaintance.

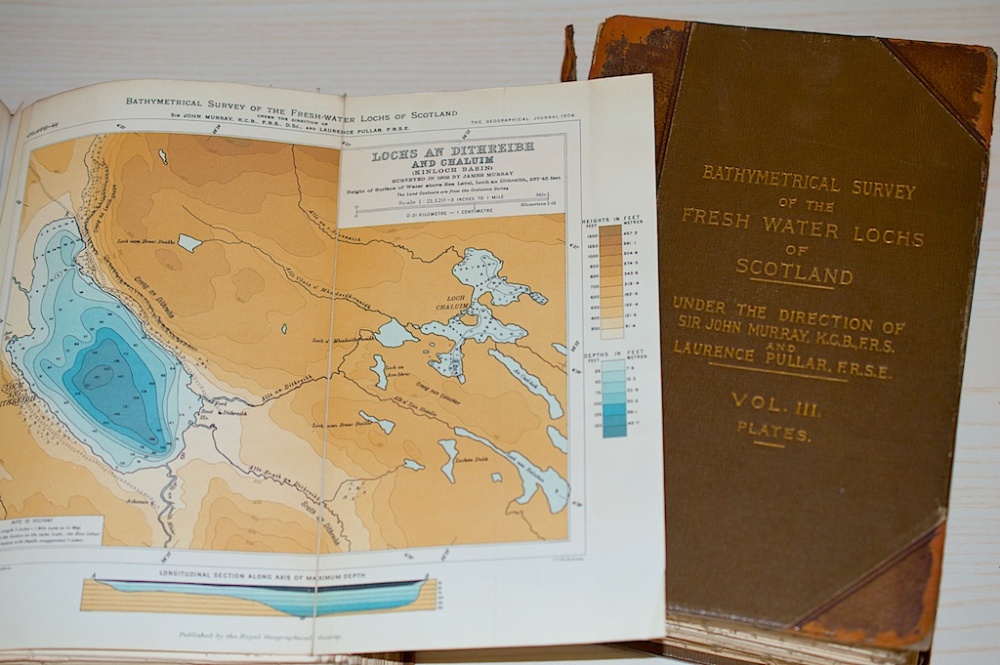

Sir John Murray’s ‘Bathymetrical Survey of the Fresh-Water Lochs of Scotland’ was published in 1910, in six volumes. The 223 beautifully drawn maps, many of them coloured, were prepared by John George Bartholomew of the famous Edinburgh map-making family. It was the first comprehensive survey of the depth and nature of Scottish lochs, and it placed Scotland at the forefront of limnology. Murray had previously done some research into the sea lochs of Scotland, and now he could compare these with freshwater lochs; he was startled by the contrasting ways in which depth affected their temperature when the surface was subjected to cold winds.

Loch Lubnaig. “Its waters cover an area of about 614 acres (or nearly one square mile)… The total number of soundings taken in Loch Lubnaig was 394, the average depth of these being 20½ feet, and the greatest depth observed being 146 feet (24⅓ fathoms).”

Loch Lubnaig. “Its waters cover an area of about 614 acres (or nearly one square mile)… The total number of soundings taken in Loch Lubnaig was 394, the average depth of these being 20½ feet, and the greatest depth observed being 146 feet (24⅓ fathoms).”

Loch Morar, complete with cross sections in both directions

Loch Morar, complete with cross sections in both directions

Tragically, Frederick Pullar, who designed the measuring device, was drowned in 1902 while trying to rescue skaters who had fallen through the ice on Airthrey Loch near Bridge of Allan. Murray was grief-stricken, and was only persuaded to continue with the survey by Pullar’s father, Laurence, who wished to see it completed as a tribute to his son.

Sir John Murray, ‘the father of oceanography’, was President of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society from 1898 until 1904. In 1910 he was presented with the Society’s Livingstone Medal “in recognition of his extensive oceanographical work, and more particularly in commemoration of the completion of his great national work, ‘The Bathymetrical Survey of Scottish Freshwater Lochs’.”

You can browse the entire work online, including the wonderful maps, via the database of the National Library of Scotland. It’s so absorbing! Here are links to:

You can browse the entire work online, including the wonderful maps, via the database of the National Library of Scotland. It’s so absorbing! Here are links to:

- Brief biographies of Murray, Pullar and other surveyors

- Notes on soundings and preparation of maps

- The maps themselves, with lochs listed A-Z and by river basin. You can zoom in for great detail or take an overview of the whole of Scotland.

Loch Tay was mapped in two sections – Upper and Lower

Loch Tay was mapped in two sections – Upper and Lower

More about seiches: “Seiches are typically caused when strong winds and rapid changes in atmospheric pressure push water from one end of a body of water to the other. When the wind stops, the water rebounds to the other side of the enclosed area. The water then continues to oscillate back and forth for hours or even days.” (NOAA, US National Ocean Service)

The phenomenon is often felt on a much larger scale. In places like the Great Lakes in North America a seiche is often whipped up by storms, and the same effect is frequently recorded throughout the world in areas of seismic activity. Sometimes an earthquake will trigger a seiche in a lake thousands of miles away, causing its waters to mysteriously recede, and just as mysteriously flow back, often in a matter of minutes. In the 18th century it was mistakenly believed that seiches were a unique feature of Lake Geneva.

The Scottish survey was by no means the end of John Murray’s illustrious career. In 1910 he spent four months on a Norwegian research vessel in the North Atlantic, taking depth soundings and noting the existence of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. He also found deposits of Sahara sand in ocean sediments. On his return he published a report entitled ‘The Depths of the Ocean’. He died in Edinburgh in March 1914, aged 73.

Quotes from ‘The Bathymetrical Survey of the Fresh-Water Lochs of Scotland’ by Sir John Murray and Mr Laurence Pullar, pub. 1910, from the archives of the RSGS.

Other sources:

- National Library of Scotland

- Scottish Geographical Journal 4:7, 345-347; 21:9, 466-484; 22:8, 407-423

- Challenger Society for Marine Science

- ‘The Depths of the Ocean‘ by Sir John Murray, 1912

- NOAA National Ocean Service (US) – explanation of a seiche

Thanks to the Archives Team at RSGS for helping me photograph some of the survey’s beautiful maps. Photos © Jo Woolf and RSGS

Photo of Sir John Murray by William Abbott Herdman from ‘Founders of Oceanography and Their Work: an Introduction to the Science of the Sea’ (1923) via Freshwater and Marine Image Bank (public domain)

What extraordinary dedication to a task. I’m so glad there are people like John Murray around because if it was left up to people like me we wouldn’t know anything. I hadn’t heard of people thinking their lochs were bottomless before, that’s a nice little bit of Scottish folklore. Another very interesting post, Jo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, Lorna, 10 years of his life, really – and the surveyors who helped him. And then he had to prepare the findings, and the maps had to be drawn… they are so incredibly beautiful, as well. Haha, the bottomless lochs! There’s the idea for a ‘Local Hero’ style film right there! 🙂

LikeLike

Well I never knew that…..words of wisdom that we perhaps all should have been aware of. Thanks for putting us straight.

LikeLike

Something I didn’t know about either, David, until I started looking! The maps are just amazing – some of them fold out to the size of a dining table. I could look at them for hours. A pleasure to share, and thanks for your comment! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank goodness for people like Sir John who are so dedicated in their quest to expand our knowledge of the world around us. (The mention of midges would have me heading for cover.) I was just reading how important these studies, done around the turn of the 19th century, are to scientists today to judge the effects of climate change. Thanks for another thorough and compelling article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s very true, Pat – he was of a generation of explorer-scientists in the late Victorian era to whom we owe so much. Their job sounds idyllic, and it does give you this lovely mental picture of rural bliss just before the Great War. Very true also about the relevance of these records today – the sheer amount of information gives such a detailed insight into temperatures, ecology, climate etc. Murray had already achieved so much with the Challenger findings, and I love how he used the same vision with the Scottish lochs.

LikeLiked by 1 person