Concluding my story about one of the world’s deepest canyons, and the men who risked their lives to explore it…

How on earth Frank Kingdon Ward survived just one of his many expeditions into the Himalayas I shall never know. If he wasn’t being pursued by a yak, he was clinging by his fingernails to a yawning precipice or wobbling precariously on flimsy rope-bridges suspended high above raging rivers. If you thought that plant collecting in the Edwardian era was a peaceful and sedentary pastime, think again.

And then there’s Eric ‘Hatter’ Bailey, the dashing young officer in the Bengal Lancers, so called by his friends who knew that his mad streak would land him in hot water… but even they couldn’t foresee his knife-edge existence as a double agent in Bolshevik-controlled Turkestan, posing as an Austrian soldier while trying to stay one leap ahead of death.

What these intrepid gentlemen have in common, apart from a charmed life and the Livingstone Medal of the RSGS, is an overwhelming curiosity about the Tsangpo Gorge and the ‘lost falls’ of the Brahmaputra.

First, let’s take a look at Frederick (Eric) Marshman Bailey…

“An absolutely first class man.”

The Viceroy of India

At the end of the Great War, when tributes to thousands of fallen soldiers were inscribed on the Menin Gate, the mother of Eric Bailey was dismayed to see her son’s name included in the list. She went straight to the War Graves Commission. “My son isn’t dead,” she told them. “He’s staying with his friend, the Dalai Lama.” Believing her to be deluded with grief, they kindly ushered her back through the door. But she was absolutely right.

Eric Bailey was a respected military officer, a gifted linguist and an expert in the art of disappearing. He had been educated at Edinburgh Academy and Sandhurst, and during the First World War he had served with the 5th Ghurkas at Gallipoli. It was only afterwards that his extraordinary talents came into their own. The ‘Great Game’ was a period of dark threats and prolonged sabre-rattling between Russia, Germany and Britain, all of whom wanted control of the Himalayan countries and ultimately the routes into India. Secret intelligence officers were worth their weight in gold, and the destiny of nations rested on their shoulders. Eric Bailey was just the man for the job.

In 1918 Bailey plunged into the turmoil of Tashkent, where the ruthless Cheka – the Bolshevik secret police – stalked the streets. His mission was to observe the Russians’ movements and send coded reports back to his base in India. He evaded capture for over a year, changing identities with the dexterity of a chameleon; if he’d been recognised, he would have been shot on sight. His escape, when it came, was worthy of any Hollywood epic. With staggering bravado, he adopted a new disguise, enlisted with the Cheka and persuaded them that he was the very man to hunt down their most wanted suspect: himself. They despatched him to Bukhara, which lay outside Bolshevik control; and after sending them an apologetic note to say that he’d already escaped, he fled over the Persian border to safety.

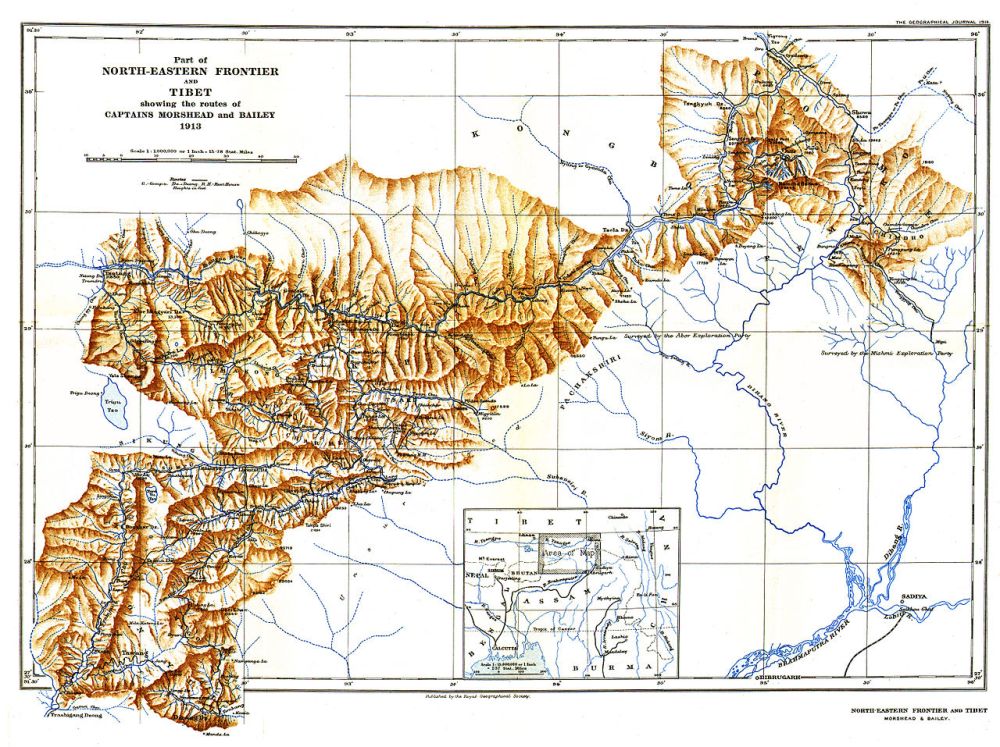

So how did Bailey come to explore the Tsangpo Gorge? In 1913, as the world trembled on the brink of war, he and a surveyor named Henry Morshead took themselves on a 1,500-mile expedition through uncharted regions of the Himalayas. Tibet was not accepting visitors, but that would scarcely have bothered Bailey. He and Morshead saw enough of the river to conclude that the Tsangpo did indeed flow into the Brahmaputra; they collected natural history specimens, recorded everything with military precision, and probably had the time of their lives. To the east of Namcha Barwa, where the river snakes around the Great Bend, they were captured and thrown into prison; but after a few days they were released.

“They saw no gigantic falls on the Brahmaputra, but at the spot where the native explorer Kinthup had located the falls the river did drop about 50 feet in 30 yards… I gather that Mrs Bailey heard nothing from her son between June 5 and November 17 – an anxious time! Still, on November 2 a friend well qualified to judge wrote to me: ‘Young Bailey will turn up all right, you will see.'”

Lt-Col A C Yate, writing in the Scottish Geographical Magazine, 1914

Beating his own perilous path through the mountain passes around the same time was a botanist named Frank Kingdon Ward. Frank was aware of Bailey’s presence in Tibet, and their paths were sometimes so close that Ward would arrive at a settlement on the heels of Bailey’s departure.

What could Ward add to Bailey and Morshead’s careful observations? Quite a lot, as it happened…

Frank Kingdon Ward

“It drives me clean daft to walk behind him… if ever I travel again, I’ll make damned sure it’s not with a botanist. They are always stopping to gape at weeds.”

Lord Cawdor, who accompanied Ward on his 1924 trek into the Tsangpo Gorge

By all accounts, Frank Kingdon Ward was a bit of a rebel even when he was a child. Wandering freely around the country lanes near his home in Surrey, he would sometimes hop over a wall and pay an unofficial visit to Windsor Castle, peering through windows and gazing upon beds “in which whole squadrons of Kings and Queens had slept.”

If Queen Victoria couldn’t keep Frank out of her garden, Tibet had very little hope of banning him from its territory, even when the penalty for trespassers was death; just like running water, he would find a way in. By 1911 Frank was already an experienced traveller, having explored the forests of Borneo and Java; and he had abandoned his day job – teaching at a public school in Shanghai – in favour of full-time adventure.

Supported by the Bees Seed Company, Frank set out in search of the rare and exquisite flowers that adorn the foothills of the Himalayas: jewel-like primulas and irises, gorgeous rhododendrons and camellias, all unknown to the western world and guaranteed to send British gardeners into transports of delight. Frank had good negotiating skills, hiring local porters to carry his supplies, and he cared little or nothing for personal comfort; but his lifelong curiosity, combined with a rather dubious sense of direction, would often lead him into danger.

Not that he seemed unduly worried:

“We climbed great precipices in search of plants, the nicest of which always select the most abominable situations, and one day in a mist I was pursued by a bull yak, and on another occasion in the forest I found myself face to face with a black bear.”

‘Wanderings of a Naturalist in Tibet and Western China’, address to RSGS reported in Scottish Geographical Journal, 1913

Cheating death became one of Frank’s specialities, and he survived an astonishing number of disasters. In 1914 a tree fell on his tent in a storm, and shortly afterwards his hut collapsed under a violent downpour. On another occasion, he saved himself from falling off a precipice only by grabbing hold of a branch; and when he tried to stop a deadly fight between two porters he found that he had become their target instead. He pulled a few ju-jitsu moves from up his sleeve, which must have startled them. His guardian angel can never have known a moment’s peace.

Despite his dedication to science, Frank was only too ready to be charmed by a romantic mystery, and the glamour of the ‘lost falls’ spoke straight to his heart. The only danger was that, having been the first to discover them, he stood a strong chance of being the first to disappear over the top.

Perhaps luckily for Frank, the reality turned out to be slightly different. In 1924 he ventured for some distance into the Tsangpo Gorge, far enough to see and name the 70-foot Rainbow Falls; but thereafter he considered the terrain to be too dangerous even for him, and he turned back. In a nice stroke of fate, it was Eric Bailey, in his role as a political officer in Sikkim, who had helped Frank and his companion Lord Cawdor by arranging their passports and encouraging them to explore an uncharted 50-mile stretch of the river.

I can’t help wishing I’d been with Frank on some of his outrageous adventures; he never seemed to be at a loss. In 1933, as a guest of the Governor of Zayul in eastern Tibet, he played the ukelele while his fellow traveller, a botanist named Ronald Kaulback, danced the Charleston and the black bottom. Frank revealed that their impromptu double act created “a huge sensation in official circles.” I bet it did. If only YouTube had been around at the time.

And then there was the awkward episode of the accidental wedding. While he was enjoying the hospitality of a Tibetan family home, Frank was alarmed to learn that he had somehow become married to the householder’s daughter during the evening. It required all his diplomacy and charm to persuade his host that the ceremony should be reversed.

So, did Bailey or Ward actually solve the riddle of the Tsangpo Gorge?

Yes… and no. They realised that the Yarlung Tsangpo flowed into the Brahmaputra, but it was several decades before anyone appreciated the true scale of the canyon. Meanwhile, they were both instrumental in bringing the glory of Himalayan blue poppies into our gardens. Bailey pressed a flower into his notebook – it was later named Meconopsis baileyi in his honour – while Ward collected seeds for cultivation. If you have a blue poppy in your garden, you have these two dashing gentlemen to thank for it!  If you missed it, read ‘The Riddle of the Tsangpo Gorge – Part One’.

If you missed it, read ‘The Riddle of the Tsangpo Gorge – Part One’.

Sources:

- ‘Wanderings of a Naturalist in Tibet and Western China’, transcript of an address by Frank Kingdon Ward to the RSGS, from the Scottish Geographical Journal, 1913

- ‘Land of the Blue Poppy – Travels of a Naturalist in Eastern Tibet’ by Frank Kingdon Ward

- Frank Kingdon Ward – biographical website by his grandson, Oliver Tooley

- Plant Explorers

- ‘Report on an Exploration on the North-east Frontier, 1913’, by Captain F M Bailey

- ‘In Russian Turkestan under the Bolsheviks’, lecture to RSGS by F M Bailey, Feb 1921

- ‘Mission to Tashkent’ by F M Bailey

- Bailey’s obituary, via Wiley Online Library

- The Scottish Geographical Magazine, 1914, 30:4, 191-197

- Volumes of newspaper cuttings in RSGS collection

All photos via Wikimedia except portrait of Frank Kingdon Ward, courtesy National Portrait Gallery

I thoroughly enjoyed this post, thank you, Jo. What a pair of extraordinary chaps. Bailey’s life reminds me of a cross between Kipling’s Kim and John Buchan’s yarns, and I love the story of him getting the job of tracking himself down, what a coup! As for Frank Kingdon Ward, I’m flabbergasted, and I like your observation that his guardian angel can’t have had a moment’s peace. Meconopsis will hold new pleasures for me now. 🙂 Your post so intrigued me that I’ve ordered Bailey’s book, ‘Mission to Tashkent’, from the library.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Lorna! It was a joy to research Ward and Bailey, and to write about them. There are so many more stories, and I have no idea how they survived to tell their tales! Yes, Bailey’s life story could be drawn from either Buchan or Kipling. I will be interested to know what you think of ‘Mission to Tashkent’. Bailey was (I think) still bound by confidentiality to some extent when he wrote it, so its effect is rather understated. You have to read between the lines! By contrast, Frank Kingdon Ward’s books are open and very entertaining. I was so delighted when I found their ‘blue poppy’ connection. I can imagine what it must have felt like, to discover such a beautiful plant growing in the wild.

LikeLike

I didn’t realise that Frank Kingdon Ward had also written books, I’ll have to check those out too, thanks. The plant hunters of that era must have had amazing experiences finding and bringing back things that had never been seen before in Britain.

LikeLiked by 1 person

He wrote quite a few books – surprisingly, because he was travelling for quite a lot of his life! The ones I’ve used for my research are ‘Land of the Blue Poppy’ and ‘The Riddle of the Tsangpo Gorges’. I’m also keeping an eye open for first editions in second hand bookshops because they are quite collectable! 🙂

LikeLike

How interesting, I’ll see if I can track any of them down in the library.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Don’t forget that on 15th August 1950 Kingdom ward was sleeping over the epicentre of the Mag 8.7 Assam earthquake. He was a friend of my parents and was missing for months. We were near Guahati at the time!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Michael, Thank you for reminding me! I had read that he had survived an earthquake, but I didn’t know that he was missing for months afterwards. That must have been terrifying. Did you ever meet Ward yourself?

LikeLike