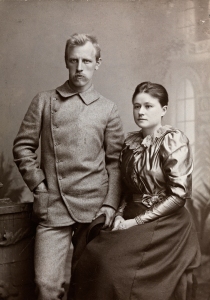

When one of his acquaintances described Fridtjof Nansen as having ‘strong elemental emotions’, they weren’t kidding. Even today, those emotions leap out of old photographs as he hits you with his bold, defiant gaze.

When one of his acquaintances described Fridtjof Nansen as having ‘strong elemental emotions’, they weren’t kidding. Even today, those emotions leap out of old photographs as he hits you with his bold, defiant gaze.

In the annals of polar exploration, that great age of endurance when everyone you can think of is a hero, Fridtjof Nansen has a legendary status that makes him the Godfather of them all. And with good reason. This young Norwegian had some crazily ambitious dreams about the Arctic, and he had the fierce determination to see them through.

It’s quite timely that I’m reading about Nansen because this month it is 120 years since he was welcomed as a guest of honour at the Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

This was a very big occasion indeed. The year was 1897, and by that time the whole world was mad about Nansen. The news of his imminent arrival in Scotland sparked such excitement among members of the RSGS that the Secretary was obliged to place a notice in the newspapers, warning them that the event had “occasioned a demand for tickets which cannot be supplied.” By 31st January more than two hundred members had put their names down for a seat at a prestigious banquet to be held in the Waterloo Rooms in Edinburgh. On 12th February, three thousand people squashed themselves into the Synod Hall, eager to hear Nansen describe his thrilling adventures in his own words. And as for the newspaper reports, I can only say that I’m awe at their thoroughness, because they have yielded some absolute gems of history that would otherwise have been forgotten.

But first I’d better tell you some more about the hero himself.

Fridtjof Nansen was born in Christiania (now Oslo) on 10th October 1861. He was the son of a lawyer with a large family and a home that was comfortable but not luxurious. On his doorstep was the Norwegian pine forest, stretching for boundless miles and inviting all kinds of irresistible adventure. Fridtjof learned to ski while still an infant, and once he was old enough he would disappear for days on hunting and fishing trips. He excelled at sport, and he relished the tough physical challenges of Norway’s climate and landscape. At school he was competent, but he just wasn’t all that inspired. There were more interesting things to do.

The elements were all there for a carefree childhood, but from an early age a shadow seemed to haunt Nansen’s soul. He described himself as having “sentimentality coupled with the coldest realism” and his biographer, Roland Huntford, draws an interesting parallel with Norway’s classical music and literature, with its stark contrasts between darkness and light. By his adolescence Nansen had an awkward feeling of being different, and would brood over unspoken things. Writing about a cross-country skiing trip, he describes the allure of a terrifying ice wall which he felt compelled to leap down, ignoring his better judgment, escaping narrowly with his life. No one, not even his parents, really understood why he courted death so often. He couldn’t really explain it himself.

Ignoring the fashion for full beards, Nansen preferred to go clean-shaven, although he did grow a flamboyant moustache. But it was his style of dress that drew the most comments. In an era of sober morning suits and frock coats he was a staunch advocate of the ‘Sanitary Woollen Clothing’ designed by Dr Gustav Jaeger* of Stuttgart. These pure wool garments were simply but finely tailored with short jackets and trousers cut daringly close to the body. Men derided him for his weirdness. Women weren’t quite so critical.

*Dr Jaeger’s name lives on in the modern fashion house.

The choice of science as a career was a decision based largely on logic. Nansen opted to study zoology at the University of Christiania, and his interest in marine organisms led to a four-month voyage into the Arctic Ocean on a ship that was called, aptly, enough, ‘Viking’. As Nansen gazed at a far distant shore he felt a new instinct stirring.

“I got the idea [to cross Greenland] one day in 1882, whilst on board a Norwegian sealing-ship [and] we were ice-bound for twenty-four days near the still unknown part of the east coast of Greenland, and from that time I could not get it out of my mind.”

Dr. Fridtjof Nansen (1889) ‘Journey across the inland ice of Greenland from east to west’, Scottish Geographical Magazine

In the 18th and early 19th century several unsuccessful attempts had been made by explorers to cross Greenland, whose interior remained completely unknown to geographers. All these expeditions had started from the west, where there were already some settlements, and had headed towards the uninhabited east. Nansen had a different idea. He decided to start from the east and head west. This way, he said, his men would have the ultimate incentive to keep going, spurred by the promise of rescue and comfort. Or, as Nansen bluntly put it:

“They had no choice, only ‘forward’. Our order was, Death or the west coast of Greenland.”

To be chosen for one of Nansen’s expeditions, you had to have a certain kind of mindset.

What gave Nansen the edge over previous explorers was his use of skis: he meant to travel light and fast, and to accomplish his trek in just one season. He consulted everyone who had any connection with Greenland, including the Swedish explorer Nordenskiöld, who had tried and failed to make the crossing in 1883. He designed a new lightweight sledge with broad runners made entirely of wood, lashed together with leather thongs. He took a look at the cumbersome old camping stoves and adapted one so that it was safer and more efficient. He ordered stocks of pemmican, which at that time was the staple food of explorers bound for extreme climates. Over 40 men offered to accompany him, and he chose three Norwegians (Otto Sverdrup, Oluf Christian Dietrichsen and Kristian Kristiansen) and two Lapps (Samuel Balto and Ole Ravna).

In the meantime, Nansen had to get himself through his University finals, which included defending his thesis in person on a public platform against the criticism of two learned and rather disapproving academics. He won his Doctorate largely through unflinching self-belief, and four days later he set sail for Greenland. Not many people thought he would come back alive.

The little party of explorers travelled north on a sealing ship, and in July 1888 they were deposited in two small boats amid the floating sea ice of Greenland’s eastern fjords. They had snowshoes, skis and sledges, but no dogs: Nansen as yet had no idea how to drive them, so the sledges had to be man-hauled.

Two and a half months later, in early October, they emerged at Godthab (now Nuuk) on the west coast of Greenland. They were forced to spend the winter there, because they had missed the last ship before the seas froze, but for Nansen that was not a problem at all. He used the time to learn the fishing and hunting skills of the Inuit, and he learned to paddle a kayak so well that he described it as “the best one-man vessel in the world.” After a jubilant homecoming in May 1889 he started to dream of an even more daring adventure, one which would bring him the hallowed prize of the North Pole.

This is where Nansen’s scientific mind and his acute observational ability gave him an edge over potential rivals. It’s likely that no one except Nansen could have come up with the idea of letting a ship freeze into the ice, and then just waiting for it to drift over the Pole. But Nansen had observed the circulating currents of the Arctic Ocean, which deposited driftwood from Siberia on the coast of Greenland, and he saw no reason why it shouldn’t work. With the help of Colin Archer, a Larvik ship-builder of Scots descent, he set about designing a vessel that would resist the impact of the ice. Put simply, her hull would be shaped like a hazelnut so that when it was squeezed at the bottom it would pop up, still intact, and ride on top of the ice. They named her ‘Fram’ which in Norwegian means ‘forward’. She would provide a safe and comfortable home for her crew as they made the strangest and surely the slowest voyage that any explorer has ever undertaken.

Nansen planned on being away for about five years. He was married by this time, and his wife, Eva, scarcely knew how to face his imminent departure. She had been a renowned classical singer before she met her husband, and now, with loneliness closing in on her, she attempted bravely to pick up the thread of her career. There was no point in waiting for communications, because there wouldn’t be any. Whether they lived or died, Nansen and his crew were on their own.

The Fram set sail from Norway in June 1893. She travelled east along the coast of Siberia, and by September she was frozen into the ice. Her hull behaved perfectly, and the drifting ice began to carry her north and west. All was going well. But after 18 months, and more importantly two interminably dark winters, Nansen began to realise that it might take even longer than he imagined for the ice to take the Fram on her wandering course over the Pole. He would have to go on foot, after all. In March 1895, together with crew member Hjalmar Johansen, he took a team of dogs, packed six sledges and lashed two kayaks to them, and set off on skis, bound for the Pole.

Once again, Nansen’s optimism is astounding. With no prior knowledge of the terrain they would face, or of the conditions that they would be expected to endure, he was confident of success. But on 7th April, as he gazed to the north and surveyed the interminable landscape of crevasses and seracs, impossible for skiiers and lethal for travellers of any kind, he made the decision to turn back. They had reached a new ‘Furthest North’ of 86°14’N. It wasn’t the Pole, but it was a considerable achievement. All they had to do was live to tell the tale.

By now the pair were isolated from their ship, which in turn was completely cut off from the outside world. It is hard, in our era of technology, to imagine what that must have felt like. They headed south, for Franz Josef Land, where they arrived in the middle of August. By that time, there was no option but to prepare for another bitterly cold winter: they built a hut, prising stones from the landscape with a broken sledge runner, and they lined it with animal skins. At least, with the abundance of marine mammals in the Arctic Ocean, they had a plentiful supply of food. Resolutely, they sat out the dark months in the hut, waiting for the return of daylight. In May 1896 they resumed their journey.

It’s unlikely that Nansen ever considered the odds of meeting another person in Franz Josef Land so on 17th June, when he spied a distant figure through on the horizon, he wondered if he was dreaming. It turned out to be Frederick Jackson, leader of a rival British expedition to the Arctic, who had set up a base on one of the islands. Nansen and Johansen were hard to recognise, with ragged hair and their faces black with accumulated grease and grime. But Jackson professed himself to be “devilish glad” to see them, and it is certain that the feeling was mutual. The men were plied with hot food, and given clean clothes and a hot bath. Their rescue was nothing short of a miracle. Jackson was on Franz Josef Land purely because he believed, according to a particularly misleading map, that he would be able to walk all the way to the Pole.

On the voyage back to Norway, Nansen and Johansen had time to prepare themselves for a tumultuous welcome. They reached Vardo on 13th August, and a week later the Fram, which had broken free from the ice, arrived in Skjaervo with her crew all safe. The men were returning heroes but Nansen in particular, being the leader, was now a celebrity the world over.

The RSGS 13th Anniversary Banquet – 13th February 1897

Among the academic institutions eager to congratulate Dr Nansen was the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, and they were delighted when he accepted their invitation to lecture in Scotland in February 1897. His impending visit provoked great excitement, and tickets to his lectures sold out almost immediately. This was, undoubtedly, the perfect time for a banquet, and on 13th February the Waterloo Rooms in Edinburgh witnessed a splendid gathering at which Nansen was the guest of honour.

260 guests assembled under the benevolent eye of the Chairman, the Marquis of Tweeddale. After the seven-course dinner, washed down with fine champagne, the toasts began. Professor James Geikie, one of the Society’s Vice-Presidents, summarised the findings of the expedition:

“There was first Nansen’s discovery of the trans-Polar current. Then there was the demonstration of a deep oceanic basin in the Polar region – a very remarkable fact. There was also the discovery of the very interesting and remarkable fact that beneath so many fathoms from the surface they had water above freezing point – relatively warm water below, with cold water above.”

Scotsman newspaper, 15.2.1897

It’s interesting to note that Nansen’s observation of surface currents led to the theory of the Ekman spiral, calculated by Swedish oceanographer Vagn Walfred Ekman.

The story of the Fram, said Professor Geikie, “would live in the history of Arctic discovery – would live to stir the blood and quicken the pulse of all good-hearted men in all time coming.”

Nansen was gracious in reply, denying that he deserved any praise, and arguing that had merely shaped a plan in his head and decided to follow it.

“I do not think it is much in favour of a man who has formed an idea that he should want to carry that idea out. The idea is, so to speak, his own child, and it is very common for men to be very fond of their own children… I think when I am praised that my comrades are much more to be praised…. My comrades believed in me and they went where most men would say there was nothing to find except death.”

Scotsman newspaper, 15.2.1897

Eva Nansen had come with her husband on his lecture tour, and she was sitting in the balcony along with the other women members of the Society. The men gave her three hearty cheers, and then Professor Geikie entertained the diners with a song which he had written especially for the occasion, entitled ‘The Cruise o’ the Fram’.

The speeches weren’t over yet. Thanks once again to Professor Geikie, whose talents and interests were extremely diverse, there was now an animated discussion about the properties of the number 13. He pointed out that the Fram had 13 crew, and that she had broken free from the ice on 13th August 1896, the same day on which Nansen arrived back in Tromso. The date of the banquet was 13th February, and it also happened to be the 13th anniversary of the RSGS. Nansen, who never left much room in his plans for superstition, gallantly got up to reply. To everyone’s delight, he revealed that on 13th December, on board the Fram, the sledge dogs had given birth to a total of 13 puppies. The general consensus was that the bad reputation of the number 13 was now laid to rest.

The banquet was a brilliant success, and the newspapers enthused about it at great length. The next day, after a sightseeing tour of Edinburgh, the Nansens continued their progress around Scotland, taking in Glasgow, Dundee and Aberdeen, where their arrival was eagerly anticipated. This wasn’t just hero-worship: it was a genuine thirst for news of fresh geographical discoveries. As you read the reports, you can still catch a whiff of the excitement, and imagine Nansen commanding the platform with the audience intent on his every word.

Fridtjof Nansen was awarded the Gold Medal of the RSGS – he was the second person to receive it, after H M Stanley.

There’s so much more to tell about Fridtjof Nansen, and it’s impossible to include it all here. He was a brilliant scientist, making some pioneering discoveries about the nervous system; and in later life he worked tirelessly to help millions of refugees, people who had been displaced by war and famine. He devised the ‘Nansen Passport’ which helped to identify and repatriate many thousands of people, and he played an important role in the League of Nations. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922.

As for the Fram, she still had adventures ahead of her: she was the vessel that carried Roald Amundsen to the Antarctic in 1910, on the expedition that gained him the South Pole.

Quotes from:

Dr. Fridtjof Nansen (1889) ‘Journey across the inland ice of Greenland from east to west’, Scottish Geographical Magazine 5:8, 393-405

Scotsman newspaper, 15th February 1897

Images of banquet menu and lecture poster reproduced with permission of RSGS. Other images in public domain.

Sources & further reading:

- ‘Nansen’ by Roland Huntford

- ‘Fridtjof Nansen – Scientist and Explorer’ by J Arthur Bain (1897)

- ‘The First Crossing of Greenland‘ by Fridtjof Nansen (1893)

- ‘Farthest North‘ by Fridtjof Nansen (1897)

- The Fram Museum, Norway

- Dr. Fridtjof Nansen (1897) ‘Some results of the Norwegian Arctic Expedition 1893-96’, Scottish Geographical Magazine 13:5, 225-246

Interesting…..that is a great ‘potted history’ of someone we are all probably aware of but not of all his life story. I guess to do what he did you have to be an individual with a driven vision that what you are doing is absolutely right. But looking about the so called greats of todays world I don’t see any that come as close to many of, lets call them, pioneers 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, David! I must admit that I knew very little about Nansen myself before coming across him at the RSGS. But what an extraordinary man. It is difficult to imagine just how completely he was cut off from the outside world, and in that way you are absolutely right, that today’s explorers don’t face the same set of challenges. I think, as science and public awareness have taken huge steps since then, the challenge of modern-day explorers has shifted – to focus awareness in a different sphere, perhaps environmental or humanitarian, alongside the advance of scientific knowledge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

1He was very handsome as well as being smart!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know! Imagine what the media would make of him today!

LikeLiked by 1 person

He would be a big hit!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m trying to imagine what it would be like to be isolated in such an extreme environment for such an extended period of time. With all the ways we have of communicating with each other these days I really can’t wrap my head around it. I’m not sure our modern minds are capable of this concept. Even when we send humans to Mars they will have contact with Earth. Thanks for another fascinating story, Jo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a difficult thing, Pat, and you are probably right that we’ll never be quite so isolated again. It’s something I often think about when I’m reading about the early explorers. Their families would have given worlds for a mobile phone! Really glad you enjoyed this, and thank you. 🙂

LikeLike

A splendid tale well told. I enjoyed that very much, thank you, Jo. The bit about the number 13 was quite a surprise. I like Nansen’s style with the Jaeger suit, rather fetching. He was his own man all right. I wonder how the rest of his family viewed him. It was a perceptive comment of his about how it was his men who deserved praise for following him and his dream. I imagine appreciating others in that way made him a good leader. It’s interesting to consider what his relationship with Johansen might have been like before and after their trip together; that sort of experience must really try a friendship. The photos are wonderful and that dinner menu is magnificent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much, Lorna. It was a job knowing where to start with Nansen – in the end I just had to plunge in somewhere! I know, the focus on the number 13 was a bit unexpected! It’s always a delight to find out what was said at these banquets. And you can see why the ladies all wanted to come and see Dr Nansen. I think, from what Roland Huntford says, that Nansen had few men friends. He found it difficult to get close to men and during his time with Johansen they never called each other by their Christian names! There was respect but not necessarily close friendship. But he appreciated the qualities of confidence and strength in his team members, and he could consider things dispassionately – that is what made him a good leader. I was very glad to find those photos of Nansen and the Fram. Yes, isn’t the banquet menu something special?! They really went to town on it. It’s wonderful to try and imagine the scene in that ballroom. Thanks again, really glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike