“On the platform was a throng of eminent men of all sorts and conditions with nothing visible but their eyes and noses above the high necks of their overcoats – for the atmospheric conditions under which the lecture was delivered were more than slightly suggestive of the polar regions – while stretching away in the semi-darkness when the cinematographer got to work was row upon row of faces gazing raptly at the lecturer. And in the midst of it all was a young man with a massive head and strong jaw, a born leader of men, and possessing an infinite belief in the ultimate dominance of his own particular star.”

Edinburgh Evening Dispatch, 19th November 1909

The evening of 18th November 1909 was bitterly cold. Two weeks of severe frost had turned the streets of Edinburgh to ice. But the weather hadn’t deterred the members of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society from setting forth on foot or by carriage towards the Synod Hall in Castle Terrace, where a very special guest was eagerly anticipated. Demand for tickets had been exceptionally high, and the lecture theatre was packed with over two thousand men and women, all of whom had forgotten their numbed fingers and toes as they feasted their eager eyes on a returning hero. His name was Sir Ernest Shackleton.

In his lifetime, Shackleton made four expeditions to the Antarctic. The first was on board the Discovery, as Third Officer under the command of Robert Falcon Scott; the second was on the Nimrod, his own expedition, funded largely by Sir William Beardmore and from which, in 1909, he had just returned. He had yet to set sail in the Endurance (1914-17), which would demand more of him and his men, physically and mentally, than he could ever guess; and he would travel to Antarctica for the last time in 1921, on board the Quest.

From the archives of the RSGS, Shackleton keeps leaping out of the page at me, but not for the most obvious reasons. Although his bravery, and that of his men, makes compelling reading, I am also fascinated by first-hand accounts of his lectures. In November 1909 he had come to Edinburgh to speak about the Nimrod expedition, and despite the weather conditions his reception was anything but frosty. He was, after all, Secretary of the RSGS in 1904 and 1905; he had lived in Edinburgh, made friends there, and also – firebrand that he was – he had electrified the hitherto sober and dignified atmosphere of the Society’s rooms in Queen Street. Less than four years later he was a national hero. It’s no wonder that the “brilliant gathering” in the Synod Hall was “uncomfortably crowded”.

From the archives of the RSGS, Shackleton keeps leaping out of the page at me, but not for the most obvious reasons. Although his bravery, and that of his men, makes compelling reading, I am also fascinated by first-hand accounts of his lectures. In November 1909 he had come to Edinburgh to speak about the Nimrod expedition, and despite the weather conditions his reception was anything but frosty. He was, after all, Secretary of the RSGS in 1904 and 1905; he had lived in Edinburgh, made friends there, and also – firebrand that he was – he had electrified the hitherto sober and dignified atmosphere of the Society’s rooms in Queen Street. Less than four years later he was a national hero. It’s no wonder that the “brilliant gathering” in the Synod Hall was “uncomfortably crowded”.

Sir Ernest’s talk was accompanied by lantern slides, and the first of these showed a map of Antarctica. “In the centre,” he said, “you see the South Pole. Now you’ve seen as much as anybody else has ever seen.” Hearty laughter greeted this opening, as he knew it would. He had an orator’s gift for dramatic effect, and his humour was timed to perfection. You can imagine his blue eyes twinkling as they skimmed the ladies in the audience. In a lecture entitled ‘Nearest the South Pole’, he was taking a bit of a risk, but he knew he could pull it off.

Shackleton then proceeded to describe the frozen seas of the Antarctic, which, in 1909, would have been almost unimaginable to anyone who had not travelled there themselves. He explained that, besides her crew, the Nimrod had carried 10 ponies, nine dogs, and a motor car – an Arrol-Johnston model, manufactured by the company of the same name, whose chairman, Sir William Beardmore, was a major sponsor of Shackleton’s expedition. Specially designed to travel on ice and snow, and surely one of the most optimistic ‘off-road’ models ever built, the car didn’t cope brilliantly well with the polar environment: Shackleton revealed, rather selectively, that “it went in a temperature of 30 degrees below zero, and did a lot of good work.”

In its advertising campaigns, Arrol-Johnston claimed that its cars offered ‘Effortless Power and Beautiful Lines’. While this might have been true on British roads, taking one to the Antarctic was rather an optimistic proposition

In its advertising campaigns, Arrol-Johnston claimed that its cars offered ‘Effortless Power and Beautiful Lines’. While this might have been true on British roads, taking one to the Antarctic was rather an optimistic proposition

In the early years of the 20th century the Antarctic continent was still largely unexplored, and the main object of the Nimrod expedition was to attain the Pole. The glory attached to such an achievement would have been immense, and but it was a wayward and deadly dream that lured many good men to their doom. Shackleton and his team had made a brave attempt:

“At 9 am on the morning of the 9th January this year, in latitude 88.23, ninety-seven geographical miles from the South Pole, they hoisted the Queen’s flag. This ceremony was thrown on the screen, and the picture was received with loud applause.”

Scotsman, 19th November 1909

To Shackleton’s enduring disappointment, his ‘Southern Party’, which consisted of Jameson Adams, Eric Marshall, Frank Wild and himself, had been forced to turn back when they were still 97 miles from the Pole. Allowing wisdom to overrule his hunger for glory, he had realised that to press any further south would have meant loss of life. Despite the fact that he had come closer to the Pole than anyone else on Earth, in his heart he still saw it as a failure. His vivacity and his showmanship, however, came to the rescue: no one who attended that lecture on 18th November would have thought, for one moment, of doubting his achievements.

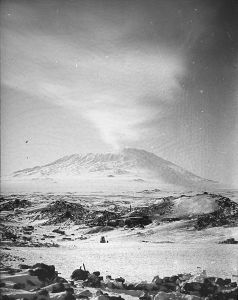

Besides the ‘Furthest South’, one of the major triumphs of the Nimrod expedition was the first ascent of Mount Erebus, which, at 12,450 feet, is the Earth’s most southerly active volcano. It took them four days, and they were hampered by blizzards; Shackleton disclosed that the temperature dropped to 62 degrees below freezing (measured in Fahrenheit). As some impressive views of the mountain were thrown onto the screen, Shackleton added that one unnamed member of the party had lost a toe to frostbite. “‘At least,’ the explorer observed dryly, ‘he has not lost it. It had to be amputated, but he keeps it somewhere in a bottle.’”

Meanwhile, another team member, Frank Wild, narrowly escaped death when a pony, which was pulling the sledge to which he was roped, fell down a 2,000-foot crevasse. Wild managed to cling on to the precipice and his friends hauled him out, along with the sledge which was carrying all their sleeping bags; but of the pony there was no sign. This was, in fact, the last pony they had, leaving them no choice but to continue under their own power.

“His sentences fell with a slow, deliberate drawl, ending often in abrupt incompleteness for lack of an accessible vocabulary; but there was something which gripped in the simple, unvarnished narrative of Antarctic horrors and hardships which might have been lost in a closely studied oration.”

Evening Dispatch, 19th November 1909

“Weird snow pictures”: According to the Scotsman newspaper, Shackleton showed a photograph of stalactites, which he observed “looked as if the family had gone through the floor”. I wondered what on earth he meant, until I came across this image from the Nimrod archive and suddenly it made sense!

“Weird snow pictures”: According to the Scotsman newspaper, Shackleton showed a photograph of stalactites, which he observed “looked as if the family had gone through the floor”. I wondered what on earth he meant, until I came across this image from the Nimrod archive and suddenly it made sense!

Shackleton described the discovery and arduous ascent of the Beardmore Glacier, which he named after his generous sponsor – or perhaps, whispered some commentators, after his sponsor’s wife, with whom Shackleton had been having a rather risky dalliance. Samples of rock were collected, and the men’s daily routine was described. With a miserable portion of half-cooked horse flesh and four biscuits as their daily ration, hunger was beginning to play with their minds, and to keep their spirits up each man would take turns in describing what he’d like to eat that day. Steak and kidney pudding, bacon and eggs, fresh rolls and butter, jam tarts and dough nuts… Shackleton smiled as he remembered, but added: “The pity and tragedy of it was that when we got back we were unable to do it.”

Photographs of a group of Emperor penguins were shown, the birds apparently listening with enjoyment to a gramophone which was emitting the strains of a popular dance tune called ‘Waltz Me Around Again, Willie’. Some of them may well have remembered the bagpipes, played to them by Gilbert Kerr on the Speirs Bruce expedition only four years earlier, and wondered why they were no longer getting any live gigs.

Through these precious reports, the spirit and comradeship of the Nimrod party comes across as vividly now as it did a hundred years ago. Shackleton was loved by his men, and he loved them in return; driven as he was throughout his life by daring aspirations, always as risky as they were alluring, he never invoked anything but loyalty and affection among those who knew him and suffered in good-hearted humour alongside him.

Through these precious reports, the spirit and comradeship of the Nimrod party comes across as vividly now as it did a hundred years ago. Shackleton was loved by his men, and he loved them in return; driven as he was throughout his life by daring aspirations, always as risky as they were alluring, he never invoked anything but loyalty and affection among those who knew him and suffered in good-hearted humour alongside him.

“In conclusion, Sir Ernest Shackleton thanked the audience for their attention. He wanted to say about the expedition that though he was the leader of it, he had with him fifteen good comrades, who worked right through for the success of the expedition. He more than any one realised his debt to those men who were with him both on ship and on shore. Whatever success the expedition had achieved was due to each individual from the lowest in rating to the highest, who worked for the good of their country regardless of themselves. This he said not only for those in command, but for all, from the youngest to the oldest.”

Scotsman, 19th November 1909

The Nimrod anchoring at Cape Royds

The Nimrod anchoring at Cape Royds

With the vote of thanks, the Earl of Camperdown, who had chaired the meeting, bestowed the Society’s Livingstone Medal on Sir Ernest Shackleton in recognition of his polar achievements. “Silver medals were presented, in their absence, to Lieut. Jameson B Adams, Dr Eric P Marshall, and Mr F Wild… In acknowledging the honour conferred upon him, Sir Ernest remarked that as secretary he had more than once brought a Livingstone Medal to such a meeting, but had never taken one away.” (Edinburgh Evening News, 19th November 1909)

After the meeting, Mrs Agnes Livingstone Bruce – daughter of David Livingstone and co-founder of the RSGS – gave a reception in honour of Sir Ernest Shackleton in the North British Station Hotel.

Sir Ernest Shackleton: Secretary of the RSGS, 1904-1905

At the RSGS, Sir Ernest Shackleton had a presence that seems to have outlived the man, because I’m always coming across something that brings him to mind. His lazy handwriting in the Council minutes book; the RSGS Prospectus for 1905, which he had lavishly embossed and ribbon-bound, raising quite a few eyebrows at the time; a bronze bust which eyes me knowingly every time I go to make a cup of tea; and of course a wealth of contemporary books and papers about his voyages to the Antarctic. As a modernising influence, I’ve got to say that he was about as welcome as a fox in a pen of chickens. He was frowned on for “lounging” in his office in a light tweed suit, which was considered way too casual by the Society’s elders; and he was responsible for installing the first telephone at their rooms in Queen Street, Edinburgh. This was perhaps the greatest outrage of them all: “You should have seen the faces of some of the old chaps when it started to ring today!” he wrote to his friend, Hugh Robert Mill.

At the RSGS, Sir Ernest Shackleton had a presence that seems to have outlived the man, because I’m always coming across something that brings him to mind. His lazy handwriting in the Council minutes book; the RSGS Prospectus for 1905, which he had lavishly embossed and ribbon-bound, raising quite a few eyebrows at the time; a bronze bust which eyes me knowingly every time I go to make a cup of tea; and of course a wealth of contemporary books and papers about his voyages to the Antarctic. As a modernising influence, I’ve got to say that he was about as welcome as a fox in a pen of chickens. He was frowned on for “lounging” in his office in a light tweed suit, which was considered way too casual by the Society’s elders; and he was responsible for installing the first telephone at their rooms in Queen Street, Edinburgh. This was perhaps the greatest outrage of them all: “You should have seen the faces of some of the old chaps when it started to ring today!” he wrote to his friend, Hugh Robert Mill.

Footnote: The Nimrod expedition was also known as the British Antarctic Expedition of 1907-1909. Shortly after his return, Sir Ernest Shackleton produced a book called ‘The Heart of the Antarctic’; one of the editions was beautifully bound in white vellum, with a flysheet bearing the signatures of all the crew members.

Further reading:

‘Shackleton‘ by Roland Huntford

‘Shackleton‘ by Roland Huntford- ‘The Life of Sir Ernest Shackleton’ by H R Mill

- ‘Heart of the Antarctic‘ by Sir Ernest Shackleton

- ‘South‘ by Sir Ernest Shackleton

- ‘The Crossing of Antarctica‘ by Lowe and Lewis-Jones

All images via Wikimedia (Creative Commons licence). Source: Archive of Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research

Another fascinating article, Jo. If I had a time machine I would definitely want to attend that meeting. If I could squeeze in. 🙂 He gets a gold star for putting the lives of his men ahead of his dreams. His heart was in the right place.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Pat! Ah yes, I would love to have been there too! Imagine the atmosphere. I agree, Shackleton deserved all the accolades he received – underneath it all he was so human and so vulnerable, and I think that’s what makes him so appealing.

LikeLike

What a wonderful occasion that lecture must have been, I can imagine squeezing in at the back of the hall, keen to hear the great man speak. It must be a constant delight to come across these fascinating documents in the RSGS archives, and I like the idea of Shackleton observing your trips to the tea caddy. That photograph of the stalactites is astonishing, I’ve never seen anything like it. Another excellent post, Jo, I always look forward to the next one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, Lorna, I would love to have been there! I loved the fact that the weather was reminiscent of the polar regions. The descriptions that you find in old newspapers are always so evocative. I loved the stalactites too – I can’t imagine how they have formed, unless it is through snow blown into an ice cave. Yes, always a delight to find these treasures, and thank you very much for your kind comment! 🙂

LikeLike

Ernest Shackleton has been my hero since 1977 when i first read Margery and James Fishers biography.For me he was the complete man.Oh to have met him.This was a MAN.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An inspirational man, and so very humble as well – so keen to give all the credit to his men. Thanks for your comment!

LikeLike