On 12th November 1904 the Royal Scottish Geographical Society held a 20th anniversary banquet at the North British Station Hotel in Edinburgh.

The menu card, one of the many treasures of the RSGS archives, was hand-painted by W G Burn Murdoch and shows Robert Falcon Scott and William Speirs Bruce together at the South Pole, raising a glass in celebration of victory as two sea lions and several adoring penguins look on. At their feet, a British ensign and Scotland’s saltire are draped behind the crest of the Society, which depicts a lion rampant on top of the globe.

The menu card, one of the many treasures of the RSGS archives, was hand-painted by W G Burn Murdoch and shows Robert Falcon Scott and William Speirs Bruce together at the South Pole, raising a glass in celebration of victory as two sea lions and several adoring penguins look on. At their feet, a British ensign and Scotland’s saltire are draped behind the crest of the Society, which depicts a lion rampant on top of the globe.

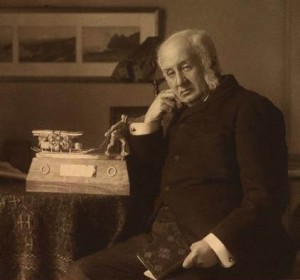

Needless to say, this isn’t how it happened at all. Speirs Bruce didn’t reach the pole, and Scott had yet to do so; in Bruce’s case, the penguins’ curiosity probably lasted until the bagpipes were played to them, and certainly no longer. But there’s another element to this prestigious occasion, and it involves the three guests of honour: their portraits are shown in small cameos on the reverse of the menu card. They were Scott, Bruce and Sir Clements Markham.

When I found this, I was excited to read about the event in the annals of the Scottish Geographical Journal. Knowing what I did about these three characters, I longed to have been a fly on the wall, just to hear what they had to say to each other. The atmosphere would have been as chilly as the ‘glacés polaires’ which were offered as dessert.

When I found this, I was excited to read about the event in the annals of the Scottish Geographical Journal. Knowing what I did about these three characters, I longed to have been a fly on the wall, just to hear what they had to say to each other. The atmosphere would have been as chilly as the ‘glacés polaires’ which were offered as dessert.

But then I read with disappointment that one of them was absent from both the banquet and the Society’s 20th Anniversary Meeting, held the day before:

“Mr Bruce, unfortunately, was prevented from being present that evening, but the members hoped soon to hear about his wonderful adventures in the Scotia. Captain Scott, however, was present, looking so well and hearty that the Antarctic regions must be a kind of sanatorium.” Scottish Geographical Journal, 1904, Vol. 20:12

You can’t help pausing for a few minutes to reflect on the unwitting irony of this, in view of Scott’s awful demise some eight years later. But the fact that Bruce was absent tells its own story. He might well have been genuinely ill; but something makes me suspect that he was not.

Born in 1867, the son of a well-to-do London doctor, William Speirs Bruce was fiercely proud of his family’s Scottish ancestry. He had a privileged upbringing, marred only by his father’s tyrannical nature; I wonder just how much this influenced his later life in terms of his relationships with others.

Born in 1867, the son of a well-to-do London doctor, William Speirs Bruce was fiercely proud of his family’s Scottish ancestry. He had a privileged upbringing, marred only by his father’s tyrannical nature; I wonder just how much this influenced his later life in terms of his relationships with others.

While Bruce was still in his teens, a spell at Patrick Geddes’ famous summer school in Edinburgh changed his attitude to life and deflected him from a medical degree towards a career in natural science. While studying in the capital, he met William Gordon Burn Murdoch, and together they ventured south into the Antarctic waters on the Dundee Whaling Expedition of 1892. Whaling expeditions were a grim but undeniably important feature of this era, thanks largely to the relentless demand for baleen or ‘whalebone‘ in corsetry. As whale numbers diminished, ships were being forced to venture further and further afield, into dangerous and uncharted waters, but the crew of a successful expedition could make a fortune on their return. To his credit, the gentle Bruce hated slaughter of all kinds, and he had signed up purely in the spirit of scientific enterprise. His official title was ship’s surgeon, while Burn Murdoch was his assistant. It was perhaps a good thing that no one was ever seriously ill on board the boat, as Bruce had only limited medical knowledge, and Burn Murdoch had none at all.

In terms of whaling, the mission was a failure: the Balaena returned to Scotland with a cargo of seal skins and a very disgruntled captain. During the voyage, he and Bruce had obviously had their moments, and many of Bruce’s natural history specimens had been surreptitiously flung overboard. Bruce complained of having to make his observations in secret, lest his records suffer the same fate. On their arrival back in Dundee, the captain tried to commandeer Bruce’s remaining collection for himself.

It wasn’t the happiest start, but it did nothing to diminish Bruce’s dreams of polar exploration.

“I am burning to be off again anywhere, but particularly to the far South, where I believe there is a vast sphere for research.” Letter to Hugh Robert Mill, from Bruce’s biography by Peter Speak

In the early 1900s, when the plans for a British National Antarctic Expedition were first mooted, there were few men more experienced and eligible to lead it than William Speirs Bruce. In addition to his whaling adventures, he had spent nearly a year at the top of Ben Nevis, living in the windswept and snowbound observatory, learning how to conduct scientific experiments and generally survive as a human being in prolonged sub-zero conditions. He had learned to sledge and ski, and his sad brown eyes and slightly stooping gait surprised those who learned that he could easily walk sixty miles in a day “without turning a hair”.

What Bruce wasn’t quite so good at was self-promotion. Although he had spent his childhood in London, he now shied away from all the social events, the clubs and restaurants and learned societies where his name would be remarked and his achievements remembered. He wrote a long letter to Sir Clements Markham, President of the Royal Geographical Society, offering his services on the ship that would set sail for the south; and Markham, to give him credit, vaguely asked Bruce to call and see him when he was next in town. The trouble was that Bruce didn’t do so. In the meantime – and, if the truth be told, long before – Markham had already singled out a leader for the expedition. He chose Robert Falcon Scott.

It was almost as if Bruce was half-expecting to be overlooked; either that, or he hung back, hoping that his reputation would do the job for him. A year later, he wrote to Markham again, but it was too late. That might have been the end of it, but for an innocent little paragraph which Bruce dropped in as an afterthought, but which must have had the effect of a well-judged hand grenade:

“I may say that I am not without hopes of being able to raise sufficient capital whereby I could take out a second British ship to explore in the Antarctic Regions.”

A second Antarctic Expedition? A rival to the glorious British enterprise? You can almost hear Markham spluttering toast crumbs over his breakfast table. It would funnel away investment, divert public attention, and, worst of all, it presented the horrible possibility of being pipped to the post. If Markham saw the South Pole in his mind at all, it probably consisted of a lonely flagstaff which was waiting for the British ensign to be hoisted with ceremonial splendour. An ex-Naval officer himself, he was jealously possessive of the team he had chosen. Unfortunately, Bruce now stood no chance of being included in it.

But Bruce was nothing if not single-minded, and life had already taught him some valuable lessons in self-sufficiency. Within a short space of time, his dream of mounting a Scottish expedition to the Antarctic was taking shape, financed largely by private sponsors such as the Coats brothers of Paisley, and supported by the Royal Scottish Geographical Society. He obtained a Norwegian whaling vessel and had her re-fitted in a Clyde dockyard; re-named the Scotia, her hull was strengthened to resist the crushing impact of ice, and a scientific laboratory was installed below decks. On the morning of 2nd November 1902 she was waved off from Troon by a typically understated farewell party which exactly suited Bruce’s nature. As handkerchiefs fluttered, the strains of ‘Auld Lang Syne’ floated across the water.

Members of the Scotia’s crew. Bruce is leaning, legs crossed and hatless, third from the right.

Members of the Scotia’s crew. Bruce is leaning, legs crossed and hatless, third from the right.

Along with Bruce himself, the Scotia carried a crew of 27, a handful of scientific staff, a taxidermist, an artist, and several dogs for sledging. Her captain was Thomas Robertson of Peterhead, one of Bruce’s friends. The Coats brothers generously stocked the Scotia‘s larder with tobacco and alcohol at their own expense; and in Dublin, where the ship called on her way south, the crew received a gift of two barrels of Guinness. In the Antarctic climate the Guinness froze, leaving only the alcohol still liquid; when opened to celebrate the passing of midwinter, this resulted in a merry occasion which was forever after remembered as ‘the night of the porter supper’.

On 6th January 1903 they reached the Falkland Islands, and by the end of March they were stuck fast in the ice around the South Orkneys, in a place they named Scotia Bay. This was far from a disaster: getting wedged in the ice was the ambition of all ship-borne polar explorers, but Bruce was disappointed that the frozen ocean offered him no prospect of going further south. Undeterred, the men went ashore on Laurie Island and set about building a land-based laboratory. Designed in the style of a Highland bothy, this would offer compact but fairly comfortable accommodation for the men who would stay here throughout the summer, and it would collect important scientific data about the continent’s climate, geology, flora and fauna. For building materials, the men used stones which they found on the island, and some of the ship’s supply of timber.

On 6th January 1903 they reached the Falkland Islands, and by the end of March they were stuck fast in the ice around the South Orkneys, in a place they named Scotia Bay. This was far from a disaster: getting wedged in the ice was the ambition of all ship-borne polar explorers, but Bruce was disappointed that the frozen ocean offered him no prospect of going further south. Undeterred, the men went ashore on Laurie Island and set about building a land-based laboratory. Designed in the style of a Highland bothy, this would offer compact but fairly comfortable accommodation for the men who would stay here throughout the summer, and it would collect important scientific data about the continent’s climate, geology, flora and fauna. For building materials, the men used stones which they found on the island, and some of the ship’s supply of timber.

The hut was named ‘Omond House’ after Robert Traill Omond, the first superintendent of the weather station on Ben Nevis

The hut was named ‘Omond House’ after Robert Traill Omond, the first superintendent of the weather station on Ben Nevis

After the long, dark winter, the sea ice began to break up again. Leaving six men safely ensconced in the hut, Bruce set sail for Buenos Aires where the Scotia stocked up on fuel and supplies. While he was there, Bruce sought out the British Consul and, through him, telegraphed the British Government to ask if they wished to lay a claim to the meteorological station that he had just established. He was eager to see his work continued, and he must have been disappointed when the reply came back as negative. He therefore handed it over to a team of Argentinian scientists, who accompanied him back to South Orkney to relieve the team of six original staff; two of these chose to remain at Omond House for another year.

Bruce’s vision was astounding. The meteorological observations which he began, and which were subsequently taken over by the Argentinian government, remain unbroken to the present day.

The Scotia’s crew at the most southerly point reached by the expedition (74°1’S 22°0’W)

The Scotia’s crew at the most southerly point reached by the expedition (74°1’S 22°0’W)

In March 1904 the Scotia sighted new territory which Bruce named Coats Land after his chief sponsors; and then, in danger of becoming stuck fast once again, the ship turned to the north, for the long voyage back to Scotland. They had been away for 16 months and, incredibly, only one life had been lost: that of Allan Ramsay, the First Engineer, who had been suffering from a heart condition. With great sadness, he was buried on the beach, facing north and the home that he had left.

“We never heard him once grumble about himself, though he was neither to hold or bend when he thought some injustice was being done to, or slight cast on, his men, on his colleagues, on his laboratory, on his Scotland. Then one got glimpses of the volcano which his gentle spirit usually kept sleeping.” John Arthur Thomson, a family friend, via Speak’s biography

Throughout the expedition, which must have presented huge challenges of strength and mental endurance, the atmosphere seems to have benefited from Bruce’s gentle influence. For a man who was never heard to swear, who sought solitude over other men’s company, and who rarely called anyone by their first name, life on board a ship might well have proved intolerable, but in fact he seems to have been an inspirational leader who loved and respected his men, and earned an exceptional degree of trust in return. He did, however, have his limits. On the homeward journey, the Scotia called at the island of St Helena:

“The shore party decided to climb the steep slope up to the site of Napoleon’s house and grave. On this occasion Bruce decided to hire a horse for the steep ascent. The rest of the party were ahead of him and hid behind a house. As Bruce approached, Kerr started up a march on the pipes, to the dismay of Bruce and his horse, which became very restless. ‘For Heaven’s sake, stop those damned pipes,’ Bruce said.” ‘Scotland and the Antarctic’, James A Goodlad

It’s quite possible that those penguins on the menu card were secretly thinking the same thing.

While Bruce and his men were busy building the laboratory on Laurie Island, the Discovery which had borne Scott and Shackleton south was already frozen into the ice at McMurdo Sound. The Scotia sailed back up the Clyde on 21st July 1904, to a hearty reception and a telegram of congratulations from Edward VII. The Discovery returned to Portsmouth less than two months later.

It is sometimes said that Bruce focused on science while Scott’s expedition was all about the glory; but this is a misconception, as the Discovery had a very full programme of scientific experiments and brought back some important findings; while Bruce, for his part, would not have scorned a chance to unfurl the Saltire at the pole, although he stated quite clearly that “no unnecessary sacrifice to the ship, or of scientific work and records” would be made in attempting to reach it. The truth is that both men were heroes, widely differing in temperament, but with the same courage and humanity at their heart. The same can be said of all the men who accompanied them.

The Scotia expedition was Bruce’s last venture into the Antarctic, although Scott travelled back there on the Terra Nova and paid the ultimate price. Instead, Bruce turned his attention towards Spitsbergen and found a powerful ally in the form of Prince Albert of Monaco, who had a keen interest in oceanography, but their plans to extract coal and minerals from the islands were scuppered first by the outbreak of the Great War and then by Bruce’s illness, which claimed his life in 1921 at the age of 54. His ashes were scattered in the sea around South Georgia.

William Speirs Bruce was honoured with the Royal Scottish Geographical Society’s Gold Medal in 1904, and his achievements earned him many other awards, although he lamented the lack of a Polar Medal; his sadness was more for the sake of his men than for himself. In 1923 the RSGS and the Royal Society of Edinburgh together inaugurated the Bruce Polar Medal, which is still awarded periodically to honour the work of young scientists in the field of polar research.

Gilbert Kerr, in full Highland dress, serenading a startled looking penguin

Gilbert Kerr, in full Highland dress, serenading a startled looking penguin

What Bruce achieved

• He explored over 4,000 miles of hitherto uncharted ocean

• He explored over 4,000 miles of hitherto uncharted ocean

• He plumbed depths up to 1,700 fathoms at a latitude of 70ºS, 17ºW

• He created a permanent weather station in the Antarctic

• He recorded 1,100 species, over 200 of which were previously unknown to science

• His crew took the first moving pictures of Antarctic wildlife: penguins in Scotia Bay

• He was a co-founder and Vice Chairman of Edinburgh Zoo, and with the help of ship-owner Edward Salvesen he brought penguins back to live in it

• He established the first Post Office in the Antarctic, and the Scotia carried its first mail

• He was the first President of the Scottish Ski Club

Bruce’s expeditions and discoveries led to the establishment of the Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory in 1906, where many of his findings were on display. Sadly, it closed in 1919.

Environmental legacy: In 2003, a modern research ship named the Scotia travelled to South Georgia and collected scientific information which was compared with Bruce’s findings, made 100 years earlier; the expedition helped to broaden our understanding of climate change over the last 20,000 years.

“His name is imperishably enrolled among the world’s great explorers, and the martyrs to unselfish scientific devotion.” Robert Rudmose Brown, botanist on the Scotia

Made by Bruce’s wife, Jessie, the expedition’s silk Saltire was displayed in several locations, including the newly discovered Coats Land on 12th March 1904

“The world shrinks, but, after all, this is only from the point of view of those who do not look into futurity. Each scientific investigation leads to the discovery of new scientific facts and problems not only unknown, but often entirely unconceived. Newer and wider fields for investigation will offer themselves in the future than in the past; rather, then, should we say, the world expands.” ‘Polar Exploration’ by W S Bruce

Sources and quotes

‘William Speirs Bruce’ by Peter Speak

‘The Voyage of the Scotia’ by Mossman, Pirie, Brown

‘Polar Exploration’ by W S Bruce

‘The Voyage of the Scotia’ from Glasgow Digital Library

Scottish Geographical Journal

Newspaper cuttings and transcripts in the archive of the RSGS

All images © Royal Scottish Geographical Society except the portrait of Sir Clements Markham which is via Wikimedia Commons

Jo, you have a way of making history come alive. I could see those toast crumbs flying! Once again you’ve introduced me to someone I want to get to know better. And I’ll be chuckling about the “porter supper” all day. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Pat! 😀 You’re very kind. Glad it gave you a chuckle, too! I must admit that I hadn’t heard of Speirs Bruce before I started writing for the RSGS. But he is a fascinating character, a real mixture of sensitivity and gritty determination. And I’d love to have seen the banquet!

LikeLike

Oh, yes! I was rather amused by the “Toast List.” I wonder if that was done to limit the toasts or to get them going. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have a feeling they went on for hours! 🙂

LikeLike

What a remarkable man, and a beautifully written biography. Another cracking read, Jo, thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, Lorna, it’s always a revelation to find out about these people. Speirs Bruce was an exceptional man, and so were all the men who went with him. Thank you so much for your kind comment!

LikeLike

As I write of Bruce, I admire his planning ability and willingness to bend dictated by conditions. The establishment of that long-term met station was a major development. Excellent images and well written. Guinness rather than the national drink?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, he had real practicality alongside his vision – a very interesting man to research. It sounds as if you ‘know’ him well yourself, and I wonder if you have published any books or papers on him? Haha, I have a feeling that the Guinness just supplemented the national drink, which would have been supplied in generous quantities by the Coats brothers! There’s a fabulous picture of a barrel of Guinness with a cloud of freezing froth emerging from it, and one of the crew trying to lick it (possibly not the best idea). I will have to have a look for that! Thank you very much for your kind comments.

LikeLike

Given the excellent outcome of this exploration with minimal loss of life, one wonders if it was wholly due to good preparation, as Amundsen undertook, or was there an extra contribution from the ship’s doctor? Do we have any details?

Thank you for such an interesting article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Michael, and thank you! That’s an interesting point, and I will check it out when I’m in the RSGS later this week and have all the sources to hand. My first thought is that there were a few factors involved – (1) that they didn’t make many long treks very far from the base, as they realised that an attempt on the Pole was not possible – so the danger of death by exposure or malnourishment was kept to a minimum; (2) that the atmosphere was generally relaxed and happy among the men, owing largely to Bruce’s leadership – this must have had an effect on their physical health as well. (3) Bruce had previous experience of the Antarctic on the Balaena (Dundee Whaling) expedition – although he did no exploring on that occasion, he knew the benefits of seal meat to prevent scurvy. I’ll see if I can find any specific details about any medical treatment and will let you know!

LikeLike

Further to the above, it seems that the crew of the Scotia remained well fed and healthy throughout the expedition, living on a diet of penguins, fish and occasional seal meat. The ship’s surgeon, Harvey Pirie, had a well stocked medical cabinet but it doesn’t seem as if he had much need to use it, except to treat Ramsay. They had regular exercise and a strict daily routine. This, and the fact that they were primarily working on a scientific mission, explains the low mortality / illness rate – or at least, in my opinion. Hope this is helpful!

LikeLike