‘Stone walls do not a prison make, nor iron walls a cage.’ Richard Lovelace

While researching the lives of those early climbers who were attracted irresistibly to the Himalayas, I have been struck by the fact that many of them still kept a special place in their hearts for the Scottish Highlands; it seems that, no matter how many other mountains they saw, no matter how daunting or compelling or thrilling, the challenge of scaling Garrick’s Shelf in Glen Coe or the north-east buttress of Ben Nevis was a precious and timeless experience, pure and deeply fulfilling, almost transcending time itself.

One of these men was William Hutchison Murray.

Some mountaineers are associated with certain peaks, meaning that their ascents have become almost synonymous with their name, but Bill’s legacy is slightly more subtle and has come down to us in a remarkable way. In fact, we’re extremely lucky that it was ever handed down to us at all.

Born in Liverpool to a Scottish family, Bill’s love affair with the mountains began in the early spring of 1934, with an ill-prepared and decidedly risky attempt on the Cobbler above Arrochar. He had never done any ice climbing, and the experience was both a lesson and a revelation. As he surveyed the pure white world from the summit, one glistening peak after another stretching away into the distance, he felt as if he had found paradise; he was only 21, but in a flash he wondered if his life would be long enough for him to savour them all to the full.

From that moment, Bill devoted every spare hour to climbing; he grew to know and love the Scottish mountains in all seasons, but particularly in winter, when the roads were empty of cars and the snow-bound hills daunted all but a handful of pioneering die-hards. This was his element. But five years later, his world changed.

“I walked across the moor in a smirr of rain and climbed the Crowberry Ridge to the summit. I remembered many days and nights on this mountain – the beauty and brilliance of moonlight, ice glinting, the climbing hard… I spent a full hour on the top – and came down as slowly as I knew how.”

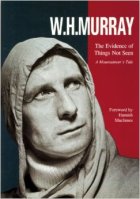

‘The Evidence of Things Not Seen’ by W H Murray

Storm clouds had been gathering in Europe for several years, and when war was finally declared on 3rd September 1939, Bill Murray bade one last lingering farewell to Buachaille Etive Mor. It was like saying goodbye to his oldest and dearest friend.

Within months he was in North Africa, an officer with the Highland Light Infantry, tasked with the daunting mission of keeping Rommel’s Panzer divisions away from the Suez Canal. Shortly after the fall of Tobruk, Murray was captured and taken away, first to a prison in Italy, and from there to concentration camps in Bavaria, Bohemia and finally Brunswick.

Faced with the prospect of months, if not years, of confinement, captive British soldiers resorted to an astonishing range of activities, some of which were carried out more openly than others. At Chieti, which was Murray’s first place of confinement, prisoners were allowed to receive parcels from home, and his mother, knowing how much he loved reading, sent him the complete works of Shakespeare. As he fingered the fine pages, Murray was struck by a sudden thought. If he swapped this paper for the horribly coarse stuff that masqueraded as tissue in the prison toilets, he would have a plentiful supply of paper on which to write.

And that is exactly what he did.

So, while his comrades had ample time to reflect on the unexpected appearance of Prospero and Portia in their daily routines, Murray began to delve deeper and deeper into the rich archives of his memory as he compiled a loving tribute to the places and the people he loved best.

“I learned from sheer necessity to live in the mind rather than the body.”

The abundance of time was always a double-edged sword in prison camps, but for Murray it allowed him to rise above the immediate physical hardships and enter a limitless world of peace and beauty. Writing became a form of meditation, and as the weeks went by he found that all his climbs in Scotland’s mountains, right down to each step and each hard-won handhold, were preserved in his memory, coming back to him “in full flood and colour”. So, as his comrades plotted together, making transistor radios and stealthily digging tunnels, Murray enjoyed a different kind of freedom.

The abundance of time was always a double-edged sword in prison camps, but for Murray it allowed him to rise above the immediate physical hardships and enter a limitless world of peace and beauty. Writing became a form of meditation, and as the weeks went by he found that all his climbs in Scotland’s mountains, right down to each step and each hard-won handhold, were preserved in his memory, coming back to him “in full flood and colour”. So, as his comrades plotted together, making transistor radios and stealthily digging tunnels, Murray enjoyed a different kind of freedom.

“In truth, I wrote with no dark design of enlightening others, but because I could not help myself. Bloodshed was forgotten awhile; once again I revelled in wholesome days, when the very air I breathed, in the company of Dunn, Mackenzie, and MacAlpine, of Bell and Donaldson, was that of rollicking adventure; when our mountaineering dreams were turbulent and our hearts high.”

‘Mountaineering in Scotland’ by W H Murray

Murray’s manuscript, carefully secreted within his battle tunic, survived a move to Moosburg concentration camp in Bavaria; but it didn’t fare so well when he was taken, two months later, to Oflag VIII F, a former Czech barracks in Bohemia. In the presence of Gestapo officers, each prisoner was thoroughly searched; and it didn’t take long before Murray’s thick wads of toilet paper were discovered. Deeply suspicious, the guards questioned him and then – mercifully – allowed him to return to his prison cell. But the manuscript was not so lucky. Murray never saw it again.

It would be wrong to say that Bill was undaunted, because he most certainly wasn’t. In addition, the worst atrocities of the war were just beginning to filter through to the prison camp where he was held. He was a gentle man, for whom peace and freedom were everything, and human suffering filled him with horror to the bottom of his soul. But he began again, and this time, when his draft was finished, he made sure he kept it well concealed.

“During this last year, I had not once thought of myself as imprisoned. I lived on mountains and had the freedom of them.”

‘The Evidence of Things Not Seen’ by W H Murray

In 1945, when the trucks of the Allied forces made their way through the prison gates, Murray and those of his friends who were still alive must have found their arrival difficult to comprehend. They were emaciated and exhausted, unwilling inhabitants of a dark world that no man should ever know. Murray’s spirit was dormant, but not dead; although physically weakened, he knew that the best therapy lay in the mountains. A few months later, as he swam in the waters of Loch Beinn a’ Mheadhoin in the Cairngorms, he weighed up the options that were open to him. His view of life had changed, and he contemplated entering a monastery.

But within a month, he had some good news. A publisher was interested in his manuscript, which now bore the title ‘Mountaineering in Scotland’. Tentatively, Murray began to accept that he might have a talent for writing; and he put his monastic ambitions on hold for just a little bit longer. The mountains were calling to him once again.

Bill Murray went on to become a much-loved writer whose gift for evoking the pure pleasure of climbing and the essence of the landscape won him many admirers all over the world. He was an important advisor for the National Trust for Scotland and a founding trustee of the John Muir Trust; he served as President of the Scottish Mountaineering Club and Chairman of the Scottish Countryside Activities Council. For his contribution to the 1951 Everest Reconnaissance Expedition, of which he was the deputy leader, he was awarded the prestigious Mungo Park medal by the Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

Bill Murray went on to become a much-loved writer whose gift for evoking the pure pleasure of climbing and the essence of the landscape won him many admirers all over the world. He was an important advisor for the National Trust for Scotland and a founding trustee of the John Muir Trust; he served as President of the Scottish Mountaineering Club and Chairman of the Scottish Countryside Activities Council. For his contribution to the 1951 Everest Reconnaissance Expedition, of which he was the deputy leader, he was awarded the prestigious Mungo Park medal by the Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

“So powerful was Murray’s eye and pen… that he could increase the aesthetic value of a landscape by writing about it.”

Murray’s obituary in The Alpine Journal, by Robin N Campbell

Bill died in 1996, just before he finished his 20th book, ‘The Evidence of Things Not Seen’, which he had been writing at his home on the shore of Loch Goil. His vision still shines through his words.

So slight were we

Who walked the edge

So brief our hold

Who had the world beneath our feet

W H Murray

Sources & further reading:

- ‘Mountaineering in Scotland‘ by W H Murray

- ‘The Evidence of Things Not Seen‘ by W H Murray

- ‘The Sunlit Summit – the Life of W H Murray‘ by Robin Lloyd-Jones

Photos of Glen Coe © Jo Woolf

Coming up… While I was reading about the wartime experiences of Bill Murray, I took an interesting diversion into a world of deception and intrigue, and in particular the very ingenious devices that were smuggled into prison camps by the British government. In my next feature, I’ll tell you about a man who escaped from captivity an astonishing 23 times… and I’ll also reveal some very clever moves in an innocent looking game of Monopoly!

What an inspiring chap. It must have been a real test of mental strength, surviving imprisonment in concentration camps. Having his first manuscript taken away and presumably destroyed must have been a crushing blow. I’ll have to see if I can get hold of one of the books you recommend. Another wonderful post, and going by your last paragraph I can’t wait for the next one. Your mention of Monopoly makes me think of dominoes, which were apparently used to pass on coded messages during World War II. Have you heard of that? I don’t know anything else about it, unfortunately.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Lorna! I was so inspired by Murray’s story, very unexpected from the little I knew of him, but so much of what he believed rings true. He wrote a book on the islands of Scotland which you may also like. If you are reading ‘The Evidence of Things Unseen’, bear in mind that the last few chapters were added after his death, or it might seem slightly odd. And yes, the whole Monopoly thing! I’ve discovered a new obsession, looking for wartime secret coding! 🙂 I hadn’t heard of dominoes being used but I can well believe it. I’ll look into that too! Looking forward to telling you more.

LikeLike

I’m not a mountaineer, Jo, but my husband was an enthusiastic climber in his youth and has scaled the heights of most of Scotland’s peaks – preferring winter for ice climbing! Now I know what to get him for Christmas – these books seem ideal . Many thanks for sharing his story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent, that’s a good idea, Marie! So glad you enjoyed Murray’s story. He was a remarkable guy.

LikeLike

I have not heard about this explorer and really enjoyed the article. I am so drawn to that last quote you included. I will have to get one of his books over my Christmas break. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome, Darlene, and thank you! I was inspired by Murray’s writing and his philosophy. I think you will enjoy his books.

LikeLike