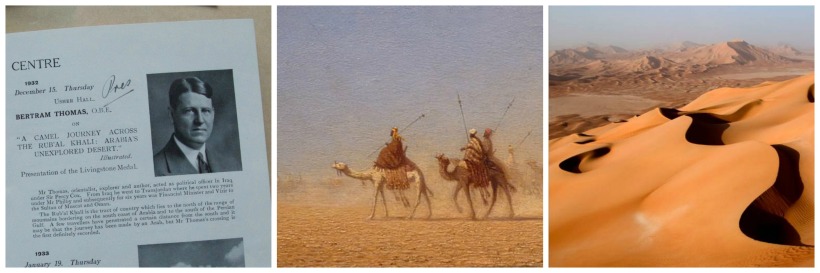

‘Camel Train in the Desert’ by Charles-Theodore Frere, 1855

‘Camel Train in the Desert’ by Charles-Theodore Frere, 1855

“Few spectacles are more moving than a large body of mounted men in the silent parts of the earth, and as I, the only European of their number, stood upright in my stirrups and looked back over the column filing past the little mosque on the edge of the palm-grove, I decided that we made a brave picture.”

In an opening address to the Royal Scottish Geographical Society’s lecture season in November 1921, the archaeologist D G Hogarth remarked that “though he had no business to urge young men to go into a country where there were several kinds of uncomfortable and untimely death, there was a great reception awaiting anyone who would do any… of the undone things in Arabia, or for the man who would cross the great Southern Desert.”

It seemed as if swashbuckling heroism was the order of the day; but 10 years later, the feat of crossing that Southern Desert – also known as the Rub’ al Khali or Empty Quarter – fell to a mild-tempered and quietly observant Englishman by the name of Bertram Thomas.

Beneath his cool and composed exterior, Thomas harboured a passion for adventure. In the Arabian desert, still a largely unexplored place of beguiling romance and mystery, he found it.

The Rub’ al Khali or Empty Quarter stretches across the bottom half of this satellite image. Encompassing about 250,000 square miles, it is the largest sand desert in the world in terms of volume, although the Sahara covers an area 15 times greater. Oases are few and far between, yielding bitter-tasting water. Waves of sand dunes rise to over 800 feet, and scattered archaeological remains lie baking in the relentless sun.

The Rub’ al Khali or Empty Quarter stretches across the bottom half of this satellite image. Encompassing about 250,000 square miles, it is the largest sand desert in the world in terms of volume, although the Sahara covers an area 15 times greater. Oases are few and far between, yielding bitter-tasting water. Waves of sand dunes rise to over 800 feet, and scattered archaeological remains lie baking in the relentless sun.

Born in 1892 in a quiet Somerset village, Bertram Sidney Thomas worked in the Post Office before signing up for service in the First World War. He was sent to Belgium and then Mesopotamia, and afterwards he accepted an appointment as Assistant British Representative in Transjordan. By 1924 he had risen to become the Wazir or Prime Minister of Muscat, and was an honoured companion of the Sultan himself.

Thomas was a natural linguist and a skilled diplomat, but there was something more: his gentle, unassuming nature seems to have won him the trust of men who looked on foreigners as outsiders – men for whom honour was everything, who lived and died by the sword. Perhaps the key was that he witnessed without judging; although, as a scientist and anthropologist, he was eager to gather information about the people he met on his travels.

In his desert companions Thomas inspired a rich but highly flammable blend of amusement and curiosity. Many saw him as irresistibly eccentric, but one of them at least perceived his destiny:

“Why aren’t you married, O Wazir?” was fired off at me by an uncomprehending Arab… I expatiated on the difficulties under which a Christian laboured, especially one serving in the East, and pointed to the comforting doctrine that for a man it was never too late. ‘Ah!’ said the Sultan, knowing of my secretly cherished desire, ‘Quite right. Insha’allah, I will help to marry you one of these days to that which is near to your heart – Rub’ al Khali.’” (‘Alarms and Excursions in Arabia’)

The Sultan might have been sympathetic, but his influence did not extend into the heart of the desert; so when the time came for Thomas to make his audacious trek he had to keep it a closely guarded secret. He had no help from the British government; in fact, they would certainly have forbidden it. To survive, he would be reliant on his own instincts and on the good will of the people he enlisted to help. This was dangerous territory that he was entering, and if he was captured or injured there would be no rescue party: no one would know where he was.

The Sultan might have been sympathetic, but his influence did not extend into the heart of the desert; so when the time came for Thomas to make his audacious trek he had to keep it a closely guarded secret. He had no help from the British government; in fact, they would certainly have forbidden it. To survive, he would be reliant on his own instincts and on the good will of the people he enlisted to help. This was dangerous territory that he was entering, and if he was captured or injured there would be no rescue party: no one would know where he was.

It was the kind of cloak-and-dagger stuff that spy movies are made of, only it was for real.

“Here, in a country the size of France and Germany together, there had never been a ruler, and social tradition was that of tribal anarchy…”

At midnight on 6th October 1930, Thomas boarded an oil tanker in Muscat. Shortly afterwards, a dhow dropped him off at Salalah on the coast of Oman. Now, he had to assemble a party of trustworthy companions and gather enough provisions to last them for the entire journey. Not surprisingly, his enquiries were greeted at first with derision and distrust… but he persisted, and two months later a train of camels set off across the Rub’ al Khali.

“Twenty-five Bedouins of the desert, none of whom he had seen before, were his companions. They struck northwards over the Qara Mountains, some 3,000 feet high, through frankincense groves and thence into the great unknown Steppe.”

Thereafter, nothing was heard of Bertram Thomas until he emerged in Doha, Qatar, on 5th February 1931. Not only had he survived unscathed, but he had had the adventure of a lifetime. He had collected over 400 natural history specimens, of which 21 species were new to science; and he had made some remarkable topographical discoveries, such as towering sand dunes and ancient tracks that his companions assured him led to the lost city of Ubar.

Although he never bragged about it, Thomas had also endeared himself to the Bedouin people:

“He was the first European to come amongst them and he won their respect by his good nature, generosity and determination. They remember him today as a good travelling companion.” Wilfred Thesiger

With determination and quiet courage, Bertram Thomas became the first European to cross the Empty Quarter, thereby answering what was known at the time as “the great unsolved question of geography”. His accomplishment is still regarded as one of the finest feats of Arabian exploration, but it is also a huge testament to his openness and humanity. He loved everything about the desert: its people, its solitude, its vast emptiness, its breathtaking landscapes and its unexpected brilliance.

“The starry sky, lighted up by the moon rising behind us, now changed to silver mirrors the little patches of water that lingered in beach depressions or wadi channels. It was fascinating, indeed, from one’s jogging camel to look down and see mirrored Venus moving straight in her course before one, skipping from pool to pool, or sailing serenely across a lagoon.” (‘Alarms and Excursions in Arabia’)

Bertram Thomas wrote several books about his travels, including ‘Arabia Felix’ and ‘Alarms and Excursions in Arabia’. He was an honoured lecturer at the Royal Scottish Geographical Society in 1932 and 1933, and was awarded the Livingstone Medal “in recognition of his valuable work and his crossing of Arabia’s unexplored desert, the Rub’ al Khali.”

“Edinburgh Presentation – Mr Bertram Thomas, the explorer, receiving from Lord Elphinstone the Livingstone Medal of the Scottish Geographical Society for exploration work in Arabia. Professor Ogilvie and Mr John Bartholomew are also seen.” Photograph published in the Scotsman newspaper, 17th December 1932; from the archive collection of the RSGS.

“Edinburgh Presentation – Mr Bertram Thomas, the explorer, receiving from Lord Elphinstone the Livingstone Medal of the Scottish Geographical Society for exploration work in Arabia. Professor Ogilvie and Mr John Bartholomew are also seen.” Photograph published in the Scotsman newspaper, 17th December 1932; from the archive collection of the RSGS.

Quotes from:

- RSGS newspaper archives (Scotsman, December 1932, containing full report of Bertram Thomas’ address to the RSGS)

- RSGS newspaper archives (Scotsman, November 1921, address to RSGS by D G Hogarth)

- ‘Alarms and Excursions in Arabia’ by Bertram Thomas (1931)

- Thomas’ obituary, by Wilfred Thesiger (1950) from the Geographical Journal via JSTOR

Further reading:

‘Arabia Felix‘ by Bertram Thomas (1932); ‘The Arabs – the Life Story of a People Who Have Left Their Deep Impress on the World‘ by Bertram Thomas (1930); Look and Learn, online magazine article

My grateful thanks to Patricia Knowles, great-niece of Bertram Thomas, who kindly allowed me to reproduce the photograph in her possession.

What a wonderfully romantic tale. A lot of these adventurous explorer chaps seem to be somewhat irascible but he sounds a very likeable fellow. It must have seemed like an eternity, the two months it took him to get his band of merry men together. I wonder if he had serious doubts about the whole thing during that time. He must have come across as confident and compelling, to have persuaded the Bedouin to accompany him. Do you know if he ever married?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, Lorna, I really enjoyed reading about Bertram Thomas and he sounds very likeable. He must have had such a belief in himself, and he seems to have been quiet but self-possessed and very determined. Yes, he did marry – in 1933 he married Bessie Hoile, and they had one daughter, Elizabeth Ann. He died in 1950, in the house where he was born.

LikeLike

I like a happy ending, thank you, Jo. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful article, Jo. Mr. Thomas would have made for a most interesting dinner companion! I love the desert, but would prefer to have a bed and indoor plumbing to return to in the evening. What an incredible journey that would have been.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Pat! Yes, I do agree with you there. I think Bertram Thomas would have been a fascinating person to talk to. And I’m with you on the indoor plumbing front as well! 🙂 But what an amazing feat, as you say – made so much more remarkable by the complete lack of communication or technological support that existed in those days.

LikeLike